\(\def\prox{\text{prox}}\) In a previous post, I presented Proximal Gradient, a method for bypassing the \(O(1 / \epsilon^2)\) convergence rate of Subgradient Descent. This method relied on assuming that the objective function could be expressed as the sum of 2 functions, \(g(x)\) and \(h(x)\), with \(g\) being differentiable and \(h\) having an easy to compute \(\prox\) function,

In the post before that, I presented Accelerated Gradient Descent, a method that outperforms Gradient Descent while making the exact same assumptions. It is then natural to ask, "Can we combine Accelerated Gradient Descent and Proximal Gradient to obtain a new algorithm?" Well if we couldn't, why the hell would I be writing about something called "Accelerated Proximal Gradient." C'mon people, work with me. Now let's get on with it!

How does it work?

As you might guess, the setup is precisely the same as Proximal Gradient. Let our objective be expressed as the sum of 2 functions,

where \(g\) is differentiable and \(h\) is "simple" in the sense that its \(\prox\) function can cheaply be computed. Given that, the algorithm is pretty much what you would expect from the lovechild of Proximal Gradient and Accelerated Gradient Descent,

Input: initial iterate \(x^{(0)}\)

- Let \(y^{(0)} = x^{(0)}\)

- For \(t = 1, 2, \ldots\)

- Let \(x^{(t)} = \prox_{\alpha^{(t)} h} (y^{(t-1)} - \alpha^{(t)} \nabla f(y^{(t-1)}) )\)

- if converged, return \(x^{(t)}\)

- Let \(y^{(t)} = x^{(t)} + \frac{t-1}{t+2} (x^{(t)} - x^{(t-1)})\)

A Small Example

To illustrate Accelerated Proximal Gradient, I'll use the same objective function as I did in illustrating Proximal Gradient Descent. Namely,

which has the following gradient for \(g(x) = \log(1+\exp(-2x))\) and \(\prox\) operator for \(h(x) = ||x||_1\),

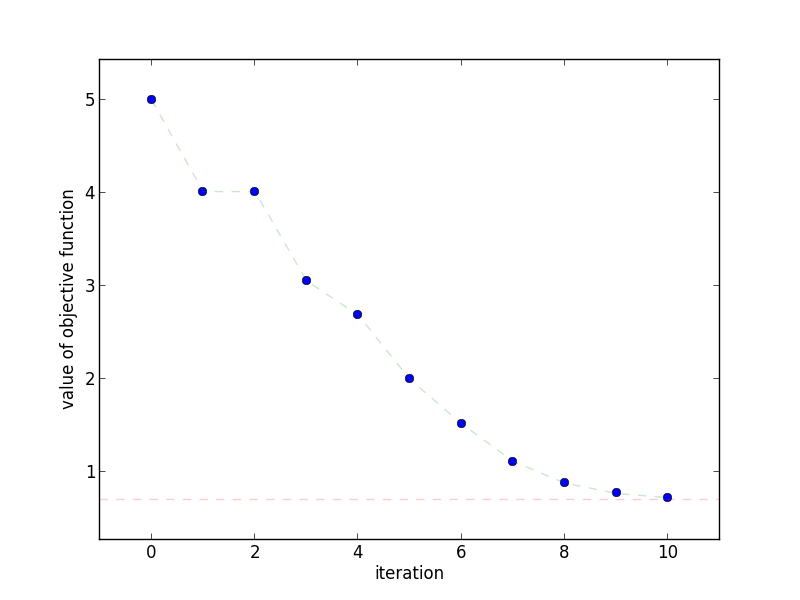

As before, we employ Backtracking Line Search to select the step size. In this example, regular Proximal Gradient seems to beat out Accelerated Proximal Gradient, but rest assured this is an artifact of the tiny problem size.

This plot shows how quickly the objective function decreases as the

number of iterations increases. Notice how the objective function doesn't

necessarily decrease at each step.

This plot shows how quickly the objective function decreases as the

number of iterations increases. Notice how the objective function doesn't

necessarily decrease at each step.

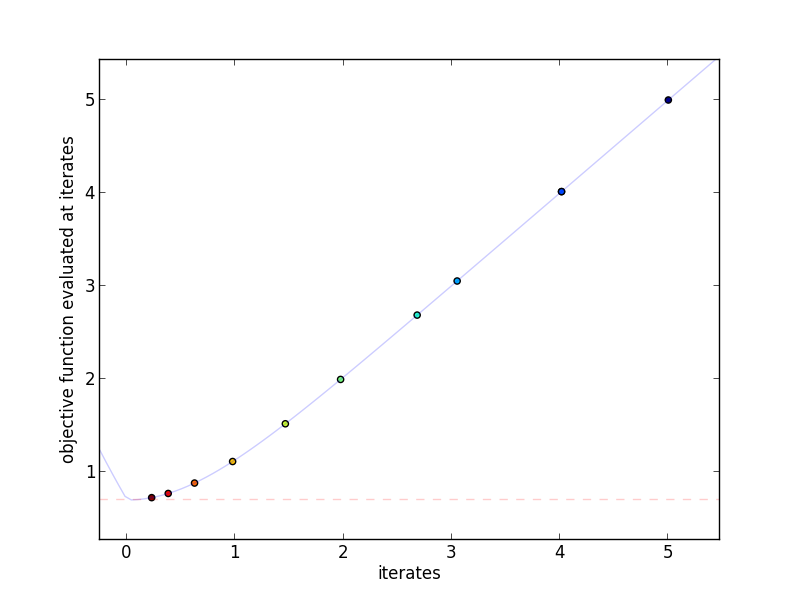

This plot shows the actual iterates and the objective function evaluated at

those points. More red indicates a higher iteration number.

This plot shows the actual iterates and the objective function evaluated at

those points. More red indicates a higher iteration number.

Why does it work?

For the proof of Accelerated Proximal Gradient, we'll make the same assumptions we did in Proximal Gradient. Namely,

- \(g(x)\) is convex, differentiable, and finite for all \(x\)

- a finite solution \(x^{*}\) exists

- \(\nabla g(x)\) is Lipschitz continuous with constant \(L\). That is, there must be an \(L\) such that,

- \(h(x)\) is convex

Proof Outline In the same way that the proof for Proximal Gradient largely follows the proof for regular Gradient Descent, the proof for Accelerated Proximal Gradient follows the proof for Accelerated Gradient Descent. Our goal is to prove a statement of the form,

Once we achieve this, the proof follows that of Accelerated Gradient with \(f \rightarrow g+h\) from Step 2 onwards.

How will we do this? As with Accelerated Gradient, we define a new set of iterates \(v^{(t)}\) in terms of \(x^{(t)}\) and \(x^{(t-1)}\) and then define \(y^{(t)}\) in terms of \(v^{(t)}\) and \(x^{(t)}\). We then exploit the Lipschitz bound on \(g\) and a particular subgradient bound on \(h\) to establish an upper bound on \((g+h)(x^{(t)})\). Finally, through algebraic manipulations we show the equation presented above, and we can simply copy-paste the Accelerated Gradient Descent proof to completion.

Step 1 Define a new set of iterates \(v^{(t)}\). As with Accelerated Gradient, we define a new set of iterates \(v^{(t)}\) and a particular \(\theta^{(t)}\) as follows,

This definition also allows us to redefine \(y^{(t)}\),

Step 2 Use the Lipschitz property of \(g\) and subgradient property of \(h\) to upper bound \((g+h)(x^{(t+1)})\). Let's begin by defining \(x^{+} \triangleq x^{(t)}\), \(x \triangleq x^{(t-1)}\), \(y \triangleq y^{(t-1)}\), \(\theta \triangleq \theta^{(t-1)}\), \(v^{+} \triangleq v^{(t)}\), and \(v \triangleq v^{(t-1)}\). From the Lipschitz property of \(g\), we immediately get,

Let's immediately assume \(\alpha \le \frac{1}{L}\), so we can replace \(\frac{L}{2}\) with \(\frac{1}{2 \alpha}\). Now let's derive the subgradient property of \(h\) we need. Recall the subgradient definition,

Now let \(x^{+} = \prox_{\alpha h}(\tilde{x}) = \arg\min_{w} \alpha h(w) + \frac{1}{2}||w - \tilde{x}||_2^2\). According to the KKT conditions, 0 must be in the subdifferential of \(\alpha h(x^{+}) + \frac{1}{2} || x^{+} - \tilde{x} ||_2^2\). Plugging this in, we see that,

We now have a subgradient for \(h(x^{+})\). Plugging this back into the subgradient condition with \(\tilde{x} \rightarrow x^{+}\),

Finally, substitute \(\tilde{x} = y - \alpha \nabla g(y)\) to obtain our desired upper bound on \(h(x^{+})\),

Nice. Now add the Lipschitz bound on \(g\) and the subgradient bound on \(h\) to obtain an upper bound on \((g+h)(x^{+})\), then invoke convexity on \(g(z) \ge g(y) + \nabla g(y)^T (z-y)\) to get rid of the linear term involving \(\nabla g(y)\),

Step 3 Use the previous upper bound to obtain the equation necessary for invoking Accelerated Gradient Descent's proof. The core of this is to manipulate and bound the following statement,

First, upper bound \(-(g+h)(x^{*})\) and \(-(g+h)(x)\) with \(z = x^{*}\) and \(z = x^{+}\) using the result of Step 2, then add zero and factor the quadratic,

Finally, use \(y = (1 - \theta) x + \theta v\) to get \(y - (1-\theta) x = \theta v\) and then \(v^{+} = x + \frac{1}{\theta} ( x^{+} - x )\) to obtain \(\theta v^{+} = x^{+} - (1-\theta) x\). Substituting these in,

Which was our original goal. We then follow the proof for Accelerated Gradient Descent with \(f \rightarrow g + h\) starting from Step 2 to obtain the desired rate of convergence, \(O(1 / \sqrt{\epsilon})\).

As a final note, you'll notice that in this proof \(\theta^{(t)} = \frac{2}{t+1}\), but in the original Accelerated Gradient proof \(\theta^{(t)} = \frac{2}{t+2}\). This ends up no mattering, as the only property we need being \(\frac{1 - \theta^{(t)}}{ (\theta^{(t)})^2 } \le \frac{1}{ (\theta^{(t)})^2 }\), which holds for either definition.

When should I use it?

As with Accelerated Gradient, the algorithm works well as long as you get the step size right. That means Backtracking Line Search is an absolute must if you don't know \(g\)'s Lipschitz constant analytically. If Line Search is possible, you can only gain over Proximal Gradient by employing Accelerated Proximal Gradient; with that said, test a Proximal Gradient algorithm first, and advance to Accelerated Proximal Gradient only if you're sure you need the faster convergence rate.

Extensions

Step Size As with Accelerated Gradient, getting the correct step size is of utmost importance. If \(\alpha^{(t)} > \frac{1}{L}\), the algorithm will diverge. With that said, Backtracking Line Search will guarantee convergence. You can find an implementation in my previous post on Proximal Gradient.

References

Proof of convergence The proof of convergence is taken from Lieven Vandenberghe's fantastic EE236c slides.

Reference Implementation

def accelerated_proximal_gradient(g_gradient, h_prox, x0,

alpha, n_iterations=100):

"""Proximal Gradient Descent

Parameters

----------

g_gradient : function

Compute the gradient of `g(x)`

h_prox : function

Compute prox operator for h * alpha

x0 : array

initial value for x

alpha : function

function computing step sizes

n_iterations : int, optional

number of iterations to perform

Returns

-------

xs : list

intermediate values for x

"""

xs = [x0]

ys = [x0]

for t in range(n_iterations):

x, y = xs[-1], ys[-1]

g = g_gradient(y)

step = alpha(y)

x_plus = h_prox(y - step * g, step)

y_plus = x + (t / (t + 3.0)) * (x_plus - x)

xs.append(x_plus)

ys.append(y_plus)

return xs

def backtracking_line_search(g, h, g_gradient, h_prox):

alpha_0 = 1.0

beta = 0.9

def search(y):

alpha = alpha_0

while True:

x_plus = h_prox(y - alpha * g_gradient(y), alpha)

G = (1.0/alpha) * (y - x_plus)

if g(x_plus) + h(x_plus) <= g(y) + h(y) - 0.5 * alpha * (G*G):

return alpha

else:

alpha = alpha * beta

return search

if __name__ == '__main__':

import os

import numpy as np

import yannopt.plotting as plotting

### ACCELERATED PROXIMAL GRADIENT ###

# problem definition

g = lambda x: np.log(1 + np.exp(-2*x))

h = lambda x: abs(x)

function = lambda x: g(x) + h(x)

g_gradient = lambda x: -2 * np.exp(-x)/(1 + np.exp(-x))

h_prox = lambda x, alpha: np.sign(x) * max(0, abs(x) - alpha)

alpha = backtracking_line_search(g, h, g_gradient, h_prox)

x0 = 5.0

n_iterations = 10

# run gradient descent

iterates = accelerated_proximal_gradient(

g_gradient, h_prox, x0, alpha,

n_iterations=n_iterations

)

### PLOTTING ###

plotting.plot_iterates_vs_function(iterates, function,

path='figures/iterates.png',

y_star=0.69314718055994529)

plotting.plot_iteration_vs_function(iterates, function,

path='figures/convergence.png',

y_star=0.69314718055994529)